The Low Moor and Clifton Colliery Tramways: History

Low Moor Tramway: Clifton Low Moor Tramway: Route Low Moor Tramway: Track & Inclines Low Moor Tramway Mapping

Low Moor Mineral RailwaysThe Centenary of the Lowmoor Iron Works was celebrated in 1891, and it is noted in "A record of the origin and progress of Lowmoor Iron Works from 1791 to 1906" [12] that the inception of the works dates from 1789, when the Manors of Royds, Hall and Wibsey were purchased from the assignees of one Squire Leedes who, having lived beyond his means, had come to grief the previous year. The entire estate, with its various rights and accessories, came into the possession of the firm of 'Hird, Dawson & Hardy'.

Oxford academic Charles Dodsworth provided a comprehensive review of the Low Moor Ironworks in the May 1971 issue of 'Industrial Archaeology', and these notes draw of this article [6]. Dodsworth records that in 179 the Low Moor estate was sold to John Hardy (solicitor), Richard Hird, John Jarratt ad the Reverend Josephh Dawson. Dawson was acquainted with Joseph Priestley, and a Unitarian Minister. at Idle, near Bradford, in 1768. Dawson was interested in science and opened pits beside his chapel, paying his miners on the Sabbeth before services started. The Bowling mines and tramways were started on the next-door lot in 1788.

Dodsworth notes that an 1811 maps shows waggonways running into the old foundry, and one, with two spurs, serving the coking area. The main line ran along New Works Road and was an iron plateway. This forled to Wibsey Slack and the other to Little Horton via ButtersA638 to a pit near Bierley ironworks.haw. It still existed in 1805. It is not known when the first rails were laid outside the works.

In 1831 a line ran from near the blast furnaces round the northern side of the works and across the present. This was the site of a latter mixed gauge line with a spur to Low Moor LYR station. It would appear that the extensive network of standard and narrow gauge lines surviving the mining field to the south dates from 1831.

An 1826-27 visit by Prussian engineers noted that the rails were rectangular bars of cast iron which had cast-on lugs for attachment to sleepers which were the usual stone pattern. Star shaped holes were made in the blocks for the rail fastenings. (As I write these notes in January 2017, the Ffestiniog has just revealed a long line of sleeper blocks still 'in situ' on the Cob at Porthmadog under the modern track).

Production ceased at the Shelf works in 1849 and the connection with the Low Moor rail system was taken out.The 1847 1st edition of the 6 inch Ordnance Survey records the development of the narrow gauge railway and tramroads linking the iron works with their mines. The Standard Gauge railways had reached Low Moor, and both sections of the works had connections to the WestRiding Union Railway via Low Moor Station. Shortly afterwards the Manchester & Leeds Railway was opened via a tunnel under the Royds Hall estate. The OS map shows that tracks had reached mines in Wyke, close to the A58 main road. In 1854 Low Moor acquired Bierley ironworks, which remained connected and in use until 1905.

Peak ironsone was 785,628 tons in 1868. In 1850 Low Moor had some 38 pits and by 1861 51, including 16 'open work'. By 1852 ow Moor had acquired collieries near Brighouse in 1852, and was mining their by 1862. Margaret Sharp [9] records that leases were signed for Hartshead and Clifton with the Armytage Estate on 28 June and 26 August 1861, these also covering assets in Cleckheaton. Another lease was signed with Jones Priestley of Lapton on 14 April 1869. The duration of the leases is not given.

The connection with the Clifton Colliery Tramway was achieved by 1886. There were various gauges in use, and sizes of waggons. Haulage was partially loco and partially assisted by 9 stationary engines. Some lines, like that joining the old and new works were mixed gauge. Dodsworth notes that Low Moor's own 3' 10.5", the Clifton 3' and Brierley (unknown) gauges were all in use up until 1928. The full extent of the system can be seen as applied to modern OS mapping here.

Locos were first used on the Low Moor lines in 1854, thought to be Standard Gauge. It will be recalled that Narrow Gauge locos at this times were still something of a novelty, although were available to power the Ffestiniog and Talyllyn Railways in 1863 and 1865 respectively. It was recommended that locos be used throughout except in the Norwood Green area but his was never done, locos only working to the yard at Cow Close Lane. Such a conversion would have required the various tunnels under the roads south of Cow Close to be rebuilt, and certain inclines, such as Clifton Common, would have been too steep for adhesion working. The Cromford & High Peak famously converted Hpton Incline, a 1-in-14 grade, to loco haulage which was much sought out by enthusiasts to watch a small steam loco blasting up this grade with very small trains. Hopton, however, had a run-up, and it is highly unlikely that Clifton Common with its 1-in-13 grade, and cold start from the Wakefield Road in Brighouse could have been successfully converted.

In 1928 Low Moor was purchased from the Receiver by Thom. W Ward, and very shortly afterwards all the Low Moor mines at Bradford, Wyke and Leeds were closed, and most then dismantled. The 36 miles of narrow gauge tramway were scraped, including the 3' 1" serving the New and Old Works, as were the standing engines. It is recalled that the last trains to run were to demolish the system. Rail haulage in the works finally ceased in 1957.

Since that period the mining operations extended a considerable distance from the Works, and ultimately covered an area of about 8,000 acres, lying in the districts of Low Moor, Bierley, Cleckheaton, Scholes, and several other adjoining hamlets, all of which were connected by a network of tramways 22 miles long (Boyes suggests a final mileage of 36 [1]), and in direct communication with the Works [12]. The company also owned ironstone mines in the townships of Beeston, Churwell, Hunslet, Osmondthorpe, and other districts around Leeds. They had 73 miles of underground roads laid with rails, and employed some 2,000 people.

In its later years Low Moor failed to update its equipment, both in the two Works and out on the tramway. Rather predictably, a large number of pits were sunk rather haphazardly across the landscape in the vicinity of the Works, and the Ordnance Survey from 1850 onwards records the rapid rise and fall of these pits and their connecting tramways. This meant that the tramway system was always been modified to suit the immediate needs of the coal and ironstone mining operations, and was never planned with the longer-term in mind. A study of the system shows long, straight runs south of Cow Close Lane, but the main line zig-zagging northwards towards the works, reflecting the older, abandoned pits that it used to serve.

The recommendation to adopt loco working throughout would have required some capital outlay but would have significantly reduced working expenses. The difficulty of a rope worked system such as Low Moor - with its 9 winding engines - is that to move a loaded train from Three Nuns to Cow Close Lane would have required four stationary engines to have been fired up and crewed, along with the ground staff required to hook on and hook off the raft of corves from the various ropes as the train progressed northwards. Finally, having arrived at Cow Close, a steam loco would have also had to have been fired up and despatched to bring the corves into the Works. Contrast that with only steaming a single loco, and which, on many industrial systems, might have only had a driver/stoker, so 'single manning' with a vengeance.

Locomotives & Rolling Stock

Given that Low Moor was famous for making locomotive boilers, fireboxes, etc. of high quality, it seems that a golden opportunity was missed, as it was another 42 years before Low Moor acquired a locomotive, which was then confined to the northern parts of the system in, and around, the actual Iron Works.

Dodsworth [6] in particular suggests that latterly the Low Moor was very conservative with its iron making technology, sticking to what it knew.

The Low Moor System had ten standard gauge locos and three 3'-10½" gauge ones. The narrow gauge locos were mainly confined to the Old and New Ironworks sites, and down to the exchange sidings (with the rope worked section) at Cow Close Lane.

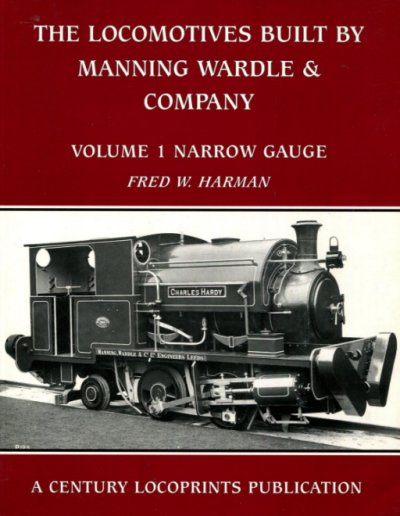

A works photo of the last of the three narrow gauge locos supplied is on the cover of "The Locomotives built by Manning Wardle & Company - Volume 1 Narrow Gauge", as shown. These were chunky looking 0-4-2 saddle tanks. A side elevation of the first loco and side and end elevations of the second are on page 30 of the same publication.

Very large dumb sprung buffers offset to the right and double coupling hooks were fitted indicating that the locos would have been used to shunt standard gauge wagons on mixed gauge track.

Norman Boyes joined the Low Moor foundry in 1930 and records the last years of the narrow gauge steam fleet within the foundry [1].

Boyes records the three Manning Wardle-built locos as:

'Lamplugh Wickham' Wks No. 1660/05 Cylinders 6.25" x 9" Driving wheels: 1'8"

'Henry Woodcock' Wks No. 1717/05 Cylinders 9.5" x 15" Driving wheels: 2'6"

'Charles Hardy' Wks No. 1924/17 Cylinders 10.5" x 15" Driving wheels: unknown

Boyes notes that the initial livery was Crimson Lake, lined red and black, and observed that 'Lamplugh Wickham' was really too small for the work offered, and could barely tackle the gradients in the Foundry yard. The Works Numbers suggest that, being the first, it was under specified, and the initial inadequacies were remedied in the second loco ordered later in the same year.

Visiting the Foundry in 1930, Boyes found the locos were very rusty, and already 'Lamplugh Wickham' was dumped at the end of a siding, and 'Charles Hardy' was out of use in the small engine shed, despite only being 13 years old. In 1934 the loco shed was converted into a garage for a lorry, and 'Charles Hardy' was relegated to a disused gantry until it and 'Lamplugh Wickham' were cut up in 1937. 'Henry Woodcock', however, continued at work until it failed boiler inspection in 1939, being cut-up in 1948. Given Ward's predilection for scrapping anything deemed surplus to requirements and the WW2 scrap drive, this was doubly odd.

In the beginning the Low Moor and Clifton tramways were separate enterprises, and it therefore follows that their fleets of waggons (corves) would have been similar but not identical. It is also known that Clifton Common tunnel had a restricted loading gauge, and therefore the Clifton Colliery corves would have been smaller, with reduced capacity. When the systems were joined up, and traffic from Three Nuns started to be routed to Brighouse via the washery at Hartshead, a fleet of smaller capacity corves was created, presumably to the same basic Low Moor design and to the Low Moor track gauge, although the scarcity of photographs of the Clifton trackage in use makes confirmation difficult.

Mention has been made of horses to move the waggons along the level sections. It is assumed that horses were used, for instance, on the Brake Head - Ox Pit section (Clifton Colliery). There was a winding engine at both ends, but the level nature of the trackbed makes this section unsuitable for conventional winding. This therefore begs the question how and when were horses provided? Just as today, the Company could have owned its own horses (and associated stabling); contracted such workings to a contractor; or hired in the horses it needed on an 'as required' basis from the neighbouring farms. The contemporaneous Ffestinog Railway is known to have contracted out its operations [20].

Jones and Dennis in their review of Ffestiniog Railway motive power [20] note that for the opening of the FR in 1836 permenant staff were employed to operate the trains, before deciding that it would be more economical or less bureaucratic to let their operations out to contract. In this early phase contracts appear to have been let to farmers, who presumably already owned suitable animals, and had the infrastructure available to service their needs. The Ffestiniog was using horse power for all its uphill traffic, with the exception of a pair of inclined planes at Moelwyn. So a steady supply of horse would have been required, which would have worked dedicated 'stages' of the railway, so a horse pulling a raft of empty waggons for five miles or so of the 13 mile route, before being replaced. The horse so retired would then be placed in a dandy waggon at the rear of a loaded downhill train and so be returned and rested before brining another rake uphill.

However, as the 'main line' was always cable worked, there would never have been the need for horses to work trains for any significant distance, except, as noted, the short sections that were on the level, and for local shunting movements. As the system was worked pretty much continuously, there would have been an on-going requirement for horse power, which could have been equally well serviced with either direct or contracted labour.

The occupants of Ox Close prior to the demolition of the 'Waggon Repair Shop' on Jay House Lane, Clifton, believed that they could see a stable formed in the eastern end by an internal partition wall by pearing through the ventilation bricks inserted in the gable end. They also believe that there was a door on the northern side of the building (so not the road side) which would have allowed entry to the stable, so lending support to the view that horses were kept at Ox Pit. There was also a small window in the eastern gable end which resembled a pay window, in the fashion of railway booking office, which was later bricked-up.

'A Record of the Origin & Progress of Lowmoor Ironworks from 1791 to 1906' [12] contains a number of shots featuring the 50cwt. corves, and it is possible to extract side and end views of the larger capacity corves. These had slopped sides and hopper doors at the bottom to allow their loads to be discharged on the gantries.

End Products

The iron was prized for its uniform and brilliant grain, commanding premium prices. The quality seemed to be due in part to the nature of the ore and coal and in part to the manufacturing process. There are - remarkably - still Low Moor made items still in frontline service, and this photo taken on 26 December 2016 shows the upper part of the firebox interior of the Ffestiniog Railway's 'Linda', fitted in June 1937. Remarkably, this loco is due to be fully overhauled in 2021, with the expectation that parts of the boiler will survive in service until 2031. When the Penrhyn Quarry sold 'Linda' and 'Blanche' to the Ffestiniog in 1963 they wanted £2,000 for 'Blanche' due to its new boiler, but only £1,000 for 'Linda' due to her 'old' low Moor boiler and firebox. The 'Blanche' was reboilered in 2017.

Photographer & copyright: JK Wallace

Also, Sharp Stewart & Co. (Builder's number 3518) for the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, B Class No. 19 (778 under the all-India number scheme) was acquired by Adrian Shooter for his private 2' gauge Beeches Light Railway in Oxfordshire. She retains her original Low Moor wrought iron boiler of 1879, the exceptions being the copper inner firebox and a small patch on the barrel. Mary Twentyman notes that the tyres on the Liverpool & Manchester Railway's 'Lion' are also from Low Moor.

The Company

Charles Dodsworth, in the May 1971 copy of 'Industrial Archaeology', noted that the company started to run into difficulty in the late 1880s, as its mines were increasingly scattered and expensive. The rail network had a variety of gauges and used a mix of stationary engines and locomotives. After the First World War the future demand for wrought iron was uncertain.

The company was taken over by Robert Heath & Sons of Staffordshire, creating a new company called Robert Heath And Low Moor Ltd. Efforts were made to reduce costs, although this affected quality. Attempts to use high-sulphur coal created serious problems and destroyed the reputation of the works as a supplier of high quality iron, while a slump in heavy industry in the 1920s further reduced demand.

In 1928 the company was declared bankrupt, and the Low Moor assets bought by Thos. W. Ward Ltd. Many of the mines, tracks and plant were closed or dismantled. Wrought iron production finally ended in 1957. As of 1971 new owners were producing alloy steel, making about 350 tons per week.

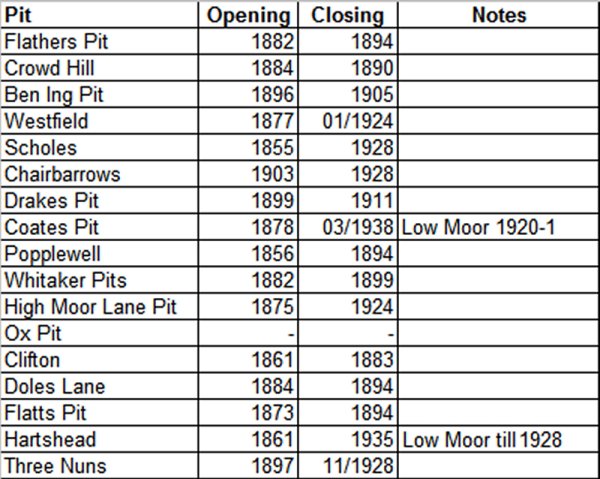

The period the various branches were in operation was determined by the opening and closing dates of the various mines. Some mine shaft were retained for drainage purposes after closure, such as the shaft at Crowd Hill retained to drain Flathers Pit. One of the problems of having mines in close proximity is that should one mine close - and cease pumping - then its neighbour is directly impacted, as it has to pump more to keep the workings clear. Consequently the second pit now finds that its costs have risen sharply, and it too closes. The Low Moor company in that respect seems to have kept a number of such 'pumping stations' to protect the remaining pits. Here is a list, extracted from the Northern Mines Research Society's interactive map, showing the opening and closing of the Low Moor mines connected to the tramway c. 1900. The properties to the east of Low Moor were not connected at this time.

Source: Northern Mining Research Society

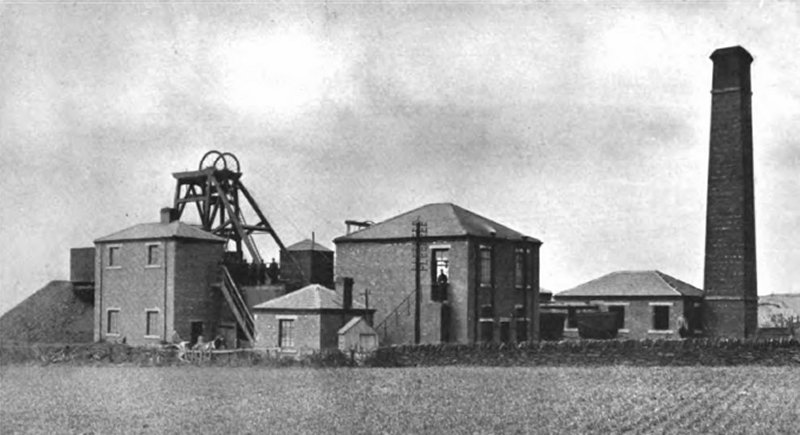

High Moor Lane colliery, Hartshead, taken from 'A Record of the Origin & Progress of Lowmoor Ironworks from 1791 to 1906'

Of note, no dates are provided for Ox Pit. The south-eastern properties, namely Hartshead and Three Nuns remained viable until the end, so ensuring that the tramway operated over its fullest extent until the acquisition by Wards.

Low Moor Tramway: Clifton Low Moor Tramway: Route Low Moor Tramway: Track & Inclines Low Moor Tramway Mapping

One might think that Low Moor missed a trick. Just 13 miles away (and a 19 minute drive by the modern M62 motorway) is the Middleton Railway, which occupies a hugely significant place in early railway development.

In many ways, the Middleton was less significant than Low Moor, as it modestly connected the mines in Middleton with the coal staithes down in Leeds. However it has a special place in locomotive development.

As 'The Rocket' was to the 1832 Liverpool and Manchester, then 'the sprocket' was to the Middleton. For in 1812 Engineer Murray designed a modest looking locomotive that was able to move loads significantly greater than its size might suggest, as the design incorporated a large cog on the side (the sprocket) which then engaged with teeth cast into the outer face of the rails.

The Middleton is also credited as being the first railway to have a fleet of locos built to the same design; the first to appoint a man specifically to drive the said locomotives; and the first to build a dedicated shed to house the loco fleet in.